One of the great things about Europe is its closely packed diversity. In the modern days of trade agreements and European Unions, crossing borders is no longer a ritual of passport-stamping. Instead, it's just like crossing state lines in the U.S.: sometimes there is a "welcome" sign but usually it's the small details that let you know you've changed jurisdictions. The order of announcements on the train shifts from German first to French then Italian; the prices are still given in Euros, but the currency changes colors. And the answer to "what's for dinner" gets completely rewritten.

We changed trains in München, upgrading from Sitzplätzen to Bettplätzen on a night train. In theory, a night train is a really groovy thing: you get on a train in one country, you fall asleep, you wake up in a different country. In practice, the sleeping part is a little different. The Bettplätzen seemed short to my six-foot self; the blankets were shorter. I found the one comfortable position possible, spred my cloak over me, and tried to find the lullaby in the roar of this mechanical beast choo-chooing its way to Italy. I remember seeing the station signs for Innsbruck, Austria in the middle of the night. And I was awake as we chugged south out of Rome, watching the ruins of ancient aqueducts looming out of the morning fog like memories.

|

The train station in Napoli (Naples), on the coast of Southern Italy, was all noise: trains and people and taxis, all coming and going. At the tourist information desk, we leaned in close to hear the bad news: there were no hotel rooms for tonight, not anywhere in Napoli. Perhaps something would open up, said the man behind the counter, shrugging. He'd make some phone calls, he said, adding our names to the waiting list and squinting past us to the growing line of travelers. Could we come back later? We shouldered our packs and stepped out of line; the information man began the same no-vacancy speech to the next people while we decided what to do.

We had come to Napoli for two reasons: pizza and Pompeii. And, if we put the packs in a locker, we could do both of those before we found a hotel room and took a shower.

Lunch first. We were looking for the best pizza in Napoli as scientifically determined by Ian on a previous visit. So, taking life in hand, we plunged into the sea of Italian traffic. In the Netherlands, drivers don't slow down for pedestrians; in Italy, not only do they not slow down, they don't stop. Pedestrians mix with bicycles and cars and delivery trucks in a strange ballet of man and machine. Italians seem to have an in-born gift for predicting speed and trajectory. I crossed the street, four lanes of traffic crowded into a two lane road, and stood on the opposite sidewalk trying to bring my panic level down. Meanwhile, little Italian grandmothers calmly crossed the street as if it were no more dangerous than a quiet stream in a back pasture.

Around the station, the streets buzzed with vehicles, the sidewalks oozed with vendors haggling with pedestrians. We walked toward the old city and, suddenly, everyone was gone. On the street where you can buy the best pizza in Napoli on any day besides Easter Sunday, the stillness was eerie; everyone in Napoli was either at the train station or at Mass. We bought gelato to console ourselves for the lack of pizza and caught a train to Pompeii.

|

When I was small, my grandparents had a subscription to National Geographic. I would reread the same two articles over and over, studying the pictures from the newly located and photographed Titanic and pouring over Pliny the Younger's excerpted account of the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. Maybe it's because I'm a native Californian, but plate tectonics, earthquakes, and volcanoes have always fascinated me. All that furious beauty! Proof we do not live on a dead rock.

The people of Pompeii didn't know their city stood at the foot of a volcano; Vesuvius was merely the mountain on the northern skyline and a good place to grow grapes. The plain at the mountain's feet had been home to an agricultural city since the 8th Century BC, and the ancient lava beds were rich and fertile; agriculture spawned trading which, in time, birthed a increasingly wealthy merchant class. Pompeii was rich, and she lived in luxury in the shadow of the volcano, a deceptively green and harmless looking mountain wrapped in an early summer haze.

|

On an unremarkable August afternoon, the mountian woke with a roar, blowing its lava plug, and proving itself a demon as it belched a towering plume of ash and gas into the summer sky. Debris rained down and buried Pompeii in pumice and ash (at an estimated 6 inches per hour!) in less than 24 hours. Those who thought to wait out the falling pumice suffocated in their homes. A wave of overheated gases sped down the mountain and over the city, fusing the ashes solid, trapping the Roman city in its own personal time capsule.

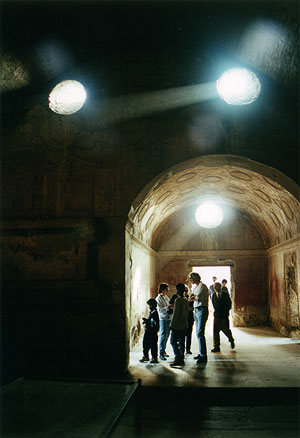

Pompeii lay forgotten for nearly 1500 years, mummified in its tomb of ash. The organic matter decomposed, leaving empty spaces in the layers of ash. When archeologists, in the continuing excavation, find one of these spaces, they fill it with plaster, then unearth the resulting "impression." The results give Pompeii a ghostly population. In the Garden of the Fugitives, thirteen human figures lay where the gases overcame them, the larger ones reaching desperately for the children dying beside them. In an otherwise empty house, a plaster cast gleams white where once a wooden wardrobe stood. A stairway strains toward the upper level, but only rises a few steps, disintegrating where it collapsed under the weight of ash above. Stepping out of the springtime sun into the cool of the shadows, I could taste the fear and panic and final resignation that filled Pompeii's last hours.

|

The emptiness of Pompeii is creepy. Most of the impressions, like the other artifacts, the minutae of daily life, have moved to museums for safe-keeping, and the tourists walk down deserted streets between remarkably well-preserved, completely empty buildings. I felt like a tresspasser, afraid that at any moment the owners of this home would return and find me, camera in hand, standing in their foyer, trying to capture the details of the floor so I could turn it into a quilt. They'd say angry-sounding things; I'd babble in English, trying to explain, before simply saying "scusi, scusi," and retreating shame-faced.

Visiting Pompeii was like entering the photographs in that old National Geographic article at my grandparent's house. I could see beyond the edges of the pictures, feel the springtime sun on my back, taste the dust of careful excavation. Walking the streets, I could hear the echos of everyday Latin conversations under the multiligual babble of tourists. Original advertisements and ancient graffiti linger on facades, preserved behind plexiglass: shop at Modesto's Bakery, vote for Lucius Ceius, for a good time, visit Corcordia.

Some 20,000 people lived in Pompeii when Vesuvius buried it, four times the population of the town where I grew up. They had running water and public toilets. There was a burgeoning middle-class busy making money and building themselves villas to rival those of the aristocracy.

|

There were stadium sporting events. Pompeii's amphitheatre is the oldest of its kind, and seated upwards of 12,000 spectators for everything from gladiatorial games to naval exercises. It also hosted "social cleansing by execution," making sport and spectacle of the deaths of early Christians.

There were fast food restaurants, businesses with an open store front and a counter with round cut-outs for holding amphorae of cold drinks and hot stews. Asellina's Thermopolium, once the Starbucks of Pompeii, offered a quick beverage to businessmen on the go. The counter is still there, carefully tiled and gathering dust, waiting for the serving girls to return.

|

Notice the evenly spaced stepping stones, a short stride apart. The streets had crosswalks, a way to negotiate steep curbs and keep a pedestrian's sandals out of the dirt. And notice the chariot wheel ruts between the stones. Even in the time of Pompeii, Italians knew about traffic.

What if Rome hadn't fallen? If Ancient Rome had avoided sliding into extravagance, trying to be young and relevant with ever more ostentation, and had withstood the barbarians, where would we be today? The time capsule of Pompeii suggests, to me at least, that this city could have held it's own against any modern metropolis. And if Rome hadn't fallen, humanity would have had 500 more years to figure out how to manage rush-hour congestion and how to share the road with multiple types of vehicles. Maybe, just maybe, we could have gotten beyond "ethnic cleansing," and we'd all be that much closer to living peaceably with our neighbors.

|

The day slid toward twilight and Pompeii's walls gleamed golden in the sunset. We followed a brown-habitted monk wearing a day-glo pink backpack out of the ruins and headed back to the train station. Along the way, we remembered my birthday (one-quarter of a century, a blink in the eye of history) and bought birthday gelato. This was Italy, after all, the land of fabulous ice cream. American ice cream, it turns out, is all about the cream; gelato is about turning up the intensity of the flavors. Pistacio gelato, for instance, is just like sitting down to a bowl of pistacios, only you don't have to shell them first.

Back in Napoli, we visited the tourist information man again. He was no longer attempting to be optimistic; there were no hotel rooms. Who'd have thought Naples was such a popular Easter destination?

We were hungry, having made most of our meals out of gelato, and needed showers. I had barely slept the night before, and we had spent the afternoon traipsing about several kilometers of ruins, enjoying an intensity of sunlight not seen since we left Santa Barbara six months before. We walked away from the information desk as the man closed his window for the night; I paused, stared at the quieting station, tried to face the possibility of sleeping on the floor and avoiding the inevitable janitorial crew, and discovered tears on my face. I mean, come on! Italy is supposed to be welcoming and romantic, not this inhospitable place. And I was going to spend my birthday on a marble floor?!? Was this going to happen everywhere? Was it such a great idea after all, this plan for touring free-form and agenda-less about Europe? Shouldn't we just go back to Rheineck now? At least there were beds and showers and a kitchen and food there. At least the terrain was familiar and the language comfortably foreign.

While I threw up my hands and called failure, Ian very calmly checked out the options: hard station floor or a bunk on a night train? The beds may be short, the blankets may be thin, but it was a bed. Tickets in hand, we found our train, bound for Milan; on board, I came undone with exaustion and relief. Other passengers peered into the compartment, looked at the four empty bunks, looked at me, and quietly went on their way.

|