Florence's claim to fame reads like a who's who from my college World Civ class. Da Vinci, inventor and painter. The Medicis, one of Europe's most ruthless ruling families. Danté, whose Inferno stabilized the Italian language and gave us metaphors we still use today. Savonarola, a Reformer a century too soon. Michaelangelo, history's greatest sculptor. Machiavelli, father of modern politicians. Galileo, who redifined the universe. Vespucci, a mapmaker who named a couple of continents. Artists, politicians, writers, explorers. The world would not be what it is today without Florence.

We arrived in the birthplace of the Renaissance without incident, after a gloriously unremarkable and uncomplicated train ride. There was even a hotel waiting for us, a room reserved while we loitered on a bridge in Venice. The hotel was surprisingly central, just a short walk from Florence's old town, well-hidden on a narrow street, the unmarked door camoflauged behind scaffolding. We walked past it twice before ringing.

Our time in Florence was a field trip, a tour to put three dimensions around the important bits of some classroom lecture. The only thing missing was the bad photocopy listing the trivia to find as we walked through the city. (In what year was Savonarola burned and where? 1498, in front of the Palazzo Vecchio.) We explored the old center of the city, stood in lines, and checked out six (!) museums.

|

We spent four hours in the rain, waiting in line outside the Uffizi, watching the street vendors try to make a sale before packing up and running from the police, only to return to try again after the law had moved on. Local artists set up impromtu studios for the line to pass through, giving us a chance to observe the works-in-progress...

|

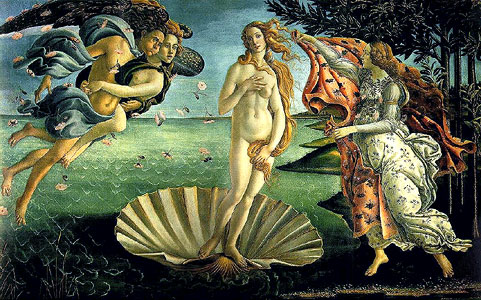

... before we visited the completed works of more famous Italians. We saw several Botticellis, including The Birth of Venus (above), a handful of Raphaels, and the only finished painting by Michelangelo to not be a permanent part of a wall.

|

At the Convento di San Marco, we toured the Dominican monestary where Fra Beato Angelico painted a fresco inside every cell. Although significant from an art history perspective as early examples of realism, I found them more impressive for their quiet devotion. They inspire contemplation and meditation as much today as they must have when Dominican brothers filled these cells.

|

We climbed the 463 stairs to the top of the dome of the Duomo (cathedral) for a top-down view of Florence and Giotto's Tower. The trek took us up close to the towering Last Judgement painted on the inside of the dome. Since Hell is at the bottom of the fresco, the route to the top passes by some very large and frightening demons, busy doing the nasty things they do best. The last stretch of stairs winds between the inner and outer shell of the dome. It's impossible, while climbing the awkward angle, to forget that on the other side of your feet is the frescoed dome and the empty space between it and the high altar at ground level; I stepped carefully from stair to stair, certain that if I did not exactly follow the steps of the person in front of me, we would all fall through the ceiling.

|

We caught our breath on the front steps of the Duomo and made some phone calls. I held the phone up as the evening bells began to ring, sharing their music with family members back in California.

|

Of course, any exploration in Florence must include Michelangeleo, Florence's favorite son. I first met this most famous of sculptors when my parents returned from a business trip with pictures of the Pieta in Rome. I loved the polished luster of the marble, the tangible sadness in Mary's outstretched hand. There is such power, such emotion, simultaneously freed from and imprisoned in that stone, I almost expected the photographs to turn, to look up.

If the power of Michelangelo's sculpture is apparent in photographs, it is overwhelming in person. Visitors crowd around David's pedistal, whispering as if afraid he might hear and rebuke us for interrupting his concentration. I would not have been the least surprised if this marble man had suddenly turned his head, stepped down and gone striding out the door in search of his Goliath, his too-large hands filled with stones and the power of God.

|

But my favorite Michelangelo in Florence is this Pieta, sculpted at the end of his life and intended for his tomb. It is in its own alcove at the Museo dell'Opera del Duomo, set apart from the other works, quiet and haunting. Sadness rolls off of it in waves. More than the grief of the narrative scene, it seems to embody the pain of an old man, driven by genius for an unobtainable perfection, desperately trying to hold on to something, creative vision perhaps, or love, as it slips away. Stepping into that alcove, I felt I was intruding, like I was forcing myself into someone else's most private moment.

|

At twilight, we made our way across the Ponte Vecchio to the Trattoria Bordino for a picturebook romantic dinner, with some of the best Italian food ever. Our post-dinner stroll, with green apple and peach gelato from Vivoli's, brought us to the now deserted courtyard of the Uffizi. We stood there under the cool gazes of Florence's Renaissance Hall of Fame, the proud and brilliant men who dragged art and science and the rest of Europe out of the Dark Ages.

Could there be another Renaissance some day? What would it look like? We wondered, would it include the ideas which had brought us to Europe in the first place? Will anyone we know make it into the World Civ lectures of the future?

|