If it was fewer clouds and warmer climes we wanted, a train to Belgium was probably not the wisest choice. We may have been going south, but we were also headed west, closer to the North Sea. The rain let up a little; the wind remained constant, biting, and chill enough to peel the skin from your face.

Despite the weather, the Belgian town of Brugge is still excessively cute. Swirling wind and tumbling rain kept me glancing at the sky, hoping or fearing to see the giant hand that was surely shaking this Sno-Globe we had stumbled into. Cobblestoned streets rim the canals weaving between narrow stone houses, each one crowned with a steep red roof. It's a picturebook city almost untouched by modernity, its 15th Century Gothic grandeur trapped in a bubble, bobbing in the flow of time.

Brugge (that's the Flemish spelling, but I use the French pronunciation, "Broozh") was a merchant town from its birth. First named by the Vikings for its wharf, the city blossomed into a early Renaissance commercial giant, trading textiles in an international market, and earning enough prestige to rival contemporary London. By the middle of the 16th century, however, Brugge's access to the sea and the trade routes had silted up; the Duke of Burgundy, the traders, and the wealth moved on, leaving the local economy in a shambles. Too poor to participate in the Industrial Revolution, Brugge languished, forgotten, as time and the world moved forward.

|

So, while the rest of Europe mechanized and modernized, Brugge didn't change. Time stood still here for almost three hundred years, and, since its discovery as a tourist destination in the 19th Century, Brugge encourages Time to move as slowly as possible. The result is a strange blend: horse-and-buggy narrow streets turned one-way automobile throughfares, hand-made lace demonstrations across the way from the mobile French fries vendor.

Our train arrived late, and we caught a taxi ride through darkened streets to the edge of town, to a private home doubling as a bed and breakfast. Morning came, with eggs delivered to our room, and we ate breakfast while studying the fat, glossy brochure, "What to See in Brugge." At just over 2 kilometers from edge to edge, Brugge is perfect for walking tours. We combined the suggested walks for a wandering route to the center of town, detouring to explore the large canal looping the city and the retired windmills pastured on its banks. Just past the windmills stands the Kruispoort, a fortified city gate once part of the Brugge's 13th Century "defensive girdle." It stands alone now, a heavy-set boxy structure in fairy-tale white stone, too delicate for soldiers and too solid for a princess, straddling a small highway, reinforced by a vanguard of trees.

|

Our walk toward the center of town took us through a canyon of stone: cobbled streets and brick facades. The only plant life was below street level, where ferns clung to canal walls and moss crept up the robes of stone saints guarding the bridges from the shifting tides. I watched the water as we walked; everything else was gray.

The treasures of Brugge, naturally, cluster around its central squares, Burg and Markt. Burg is the civic center, home of the city's history and the oldest city hall in the Low Countries, built in the early 1400's. It's a very pointy building, with a steep roof, several spires, and every available horizontal edge made serrated with ornate Gothic crusties. These statues (at left), unnamed saints stacked three deep between the Hall's towering windows, struck me as somewhat out of place. Their edges are rough and the details are crude; on a building so ornate, these guardians leap out at you, forbidding you to disturb Brugge's collected history on their watch.

|

In a corner of Burg Square, beneath a facade blackened with time and glittery with gold statues (pictured at right), a split level church hides behind a series of enormous Romanesque pillars. The lower level is Saint Basil's Chapel, built in the 12th century and extremely dark behind its heavy walls. Just standing inside is enough to transport you to the Middle Ages, when living to age 30 was a challenge, when religion and knowledge both were mysteries, and the hand of God might smite an entire city with plague for one man's sin.

Upstairs, the atmosphere is a bit lighter. "Converted to Neo-Gothic style in the 19th century," this is the Basilica of the Holy Blood, the resting place of a jewel-encrusted hexagonal vial, the Relic of Christ's Blood. Brought to Brugge circa 1150, after the Second Crusade, the Relic still makes its way through the streets of Brugge every year on Ascension Day. There are stories of at least two miraculous re-liquifications of the Blood since its arrival here. (It did not bother to re-liquefy for us, choosing to remain dry and a faded brown. I suppose it needs a better reason than the curiousity and skepticism of a couple of travelers.)

One block away to the northwest of Burg Square's dignified saints and relics, Markt Square is exactly what it sounds like, the market square, bustling and noisy. Once home to Brugge's thriving cloth trade, this is the business center, now ringed with restaurants and shops catering to the tourists. (Hoping to blend in a little, we skipped the tourist-centric Square and had lunch off of Markt at Lotus, a "Natuur Restaurant." The pre-determined menu of steamed grains with mushrooms was just the sort of thing I'd expect to find in Santa Cruz, but the frothy glasses of freshly pressed apple and ginger juice are definitely worth the trip.)

|

On the south side of Markt, Brugge's "most remarkable landmark," a squat building with a sudden burst of stone just missing vertical in its reach for the wind-scrubbed sky, watches over and directs the ebb and flow of business. Built in the early 1300's, extended in 1486, the Belfry is 83 meters tall, 366 steps sprialling up the squared tower. The way up is tight in the corners, where you stand on your toes and press yourself against the wall to let someone pass. The straight stretches are just slightly more spacious; you only have to turn sideways to pass the decending traffic.

The view from the top is stunning, of course. Had the wind been more vigorous about clearing the clouds from the sky instead of trying to get inside my coat, we would have been able to see to the coastline, to match the landmarks with the reference plaques along the railing. Just in case the wind ever decided to be very thorough, the plaques included directions and distances to more far off places; London, so many kilometers to the northwest, Paris, so many more kilometers to the south. Of course, should the wind ever be so strong, they'll have to install trampolines and safety nets below the tower. In its present state, the wind was enough to encourage constant use of the handrails.

|

|

|

|

But the true highlight of the Belfry is not the view, however stunning it might be. No, the treasure is inside, one floor up from the medieval treasure room.

It's a carillion, a gigantic music box, with 47 bells weighing in at a total of 27 tons, ranging from the tiniest sopranos to the bass bells I could have stood inside. Every fifteen minutes it plays something sweet and joyful, a different piece, each a little longer than the last, building up to the three-minute carol sounding on the hour. We stood under the bells, exposed to the wind, aware of the time. They surprised me anyway, ringing out their music for all of Markt, echoing somewhere in my middle.

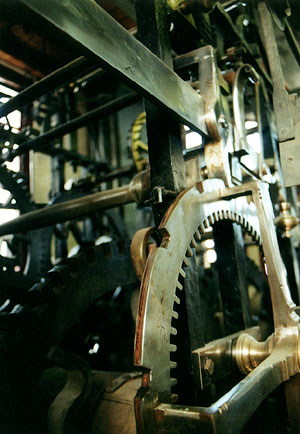

Inside the belfry, on the next level down, a drum, pegged with the cues for the bells, rotates at the clock's command. The pegs catch and move hammers as the drum turns; the hammers pull and release the clappers to sound the bells. When I was small, I knew of a special music box with a pane of glass over the mechanics. I could wind it and watch how it worked, know where the music came from. Standing in Brugge's Belfry was like shrinking small enough to stand inside that music box, to hear the music bold and strong, as it should be.

|

Back at ground level, we sampled the local snack, "frites," something bearing an uncanny resemblance to French fries, but much yummier than the limp or overdone things at the local McDonald's. For one, you can tell that frites come from actual potatoes. They are served in a paper cone, somehow looking both far too large and not nearly big enough, with a tiny wooden pitchfork-shaped utensil. Topped with ketchup, mayonnaise, (It sounds awful, but "mayonnaise" in Europe is different than the jar of Miracle Whip or Best Foods in your fridge.) and onions, it's a warm snack that's almost a meal. Quick and easy and finger-friendly, a cone of frites is just the thing for a no-time-for-a-meal meal when you're rushing between appointments or dashing to make showtime at the theatre.

So, we sat in the middle of Markt, using a too-small statue for windbreak, dined on frites and listened to the carillion singing out the quarter hour. An American couple approached us, asking if we would take their picture with the belfry as backdrop, then insisted on returning the favor. The result turned out rather nicely, I think. We may actually look warmer than we were.

|

Because twilight was stretching out our wind-blown shadows, and because we were tourists, we hired one of the horse and buggies loitering in Markt for an evening highlight drive around Brugge. Our driver stopped long enough to water the horse outside a convent, releasing his passengers for a quick exploratory peek inside the convent walls. It is a sweet and simple place, originally founded in 1245 as a Beguinage, a residence for unmarried medieval women who did not wish to make the vows of a nun. Today, the sisters of St. Benedict's order live here. Their home is one of the most beautifully peaceful places in Brugge. No cars, no horses, no buggies are permitted in the circle of simple homes ringing a park liberally carpeted with daffodils. By the gate, there is a small sign requesting silence as you walk through the grounds. I don't think we were silent enough; doves fluttered and rustled as we walked by but made not a sound when a sister passed on her way to the chapel in the corner.

Our buggy driver returned us to Markt, where we discovered a chocolate shop. Our guidebook claims that chocolate is one of the two most celebrated things about Belgium, so it seems a bit strange that it took us all day to find a chocolate shop. We bought two of each available truffle, much to the amusement of the girl behind the counter. They were exquisitely chocolate, delicately decorated, filled with cremes and liquors... It was surely a record display of will-power (or an awareness that there will be no more until we return to Brugge) that made those truffles last for almost 18 months.

The next morning, we called a taxi for a ride to the train station. Our little week-long vacation had run out; it was time to head home to our castle on the Rhein and the familiar rhythms of German life. Perhaps there would be new developments awaiting us. Perhaps, at the very least, we would drag a little Low Country Spring back with us.

|