Our train from Belgium arrived late in Bad Breisig. We stood at the Bahnhof (train station) on the edge of town, the lights flickering over quiet streets, the stillness broken only by the occasional car on the highway. No one at Rheineck answered their phones, and after several vain attempts, we decided the taxi phone at the Bahnhof was out of service. It wasn't a surprising discovery; I think there is one taxi driver for all of Bad Breisig, operating out of his home. He probably calls it a night just after sundown on weekdays. Then again, maybe he only drives by appointment; that was certainly the only time we ever saw him.

There was nothing to do except start walking. We could have waited until someone answered our phone calls, but that would probably mean waiting until lunchtime tomorrow. And, having already tested the steps at the train station and declaring them "cold and uncomfortable," staying there was out of the question. We may have left the North Sea wind behind in Belgium, but it wasn't anywhere close to being a warm night in Germany. So, we hitched up our backpacks and headed home, walking along the deserted highway, crossing the silent railroad tracks, passing the last working streetlight at the bottom of Rheineckweg. Starlight shone through the leafless branches above, casting only enough light to make some shadows a shallow gray against the black of the rest. We shuffled our feet over the cobblestones and wound our way uphill until we rounded the last corner to find the gate and the first lights of home.

|

In the morning, we discovered everything was different and nothing had changed, despite our week of travel. The remodeling and modernization of Rheineck continued at a snail's pace. As a national landmark, the castle appeared on the radar for several bureaucracies, and each had regulations and paperwork for every small detail. One group wanted the buildings brought up to modern fire safety codes; another threatened havoc if anyone made any changes to the exterior or the roofline, insisting that Rhieneck should appear unchanged when viewed from town or from across the river. Inside, they figured we could do whatever we wanted. The central stairway was finally refinished, stripped of its faded carpet and restored to a rich, gleaming brown. The entryway remained cold and bare, the stained drapes still framing the windows. Upstairs, the dining room was shrouded in plastic in preparation for refinishing the floor and installing the new kitchen. The breakfast nook was still the place for tea and meetings; you just had to negotiate the layers of plastic to go between the table and the refrigerator.

|

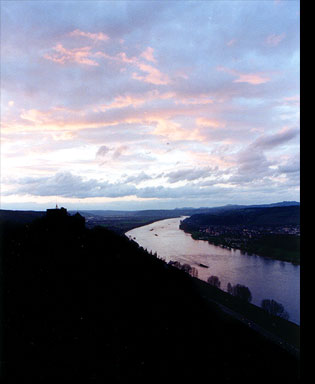

But, joyfully, the weather was warmer. Winter's constant layers of overcast peeled away from the sky, one by one, revealing familiar blue still lingering behind the clouds. A haze of green hovered around the tips of branches on trees and shrubs. I stood in our bathroom, holding open the window in the sloping ceiling, my head and shoulders above Rhieneck's slate roof, listening to birdsong and the sound of churchbells echoing in the valley. I sat in our windowsill and stared outside, praying for flowers. For the first time in my life, I wanted a space to plant things. Instead, I took up talking to the plants, encouraging new leaves, begging flowers to bloom. This must be what they meant when they invented the phrase "spring fever."

|

To distract me from the lack of a garden of my own, we took up walking nearly every day. We walked through woods suddenly magical in the afternoon light, the new growth in the trees making the very air seem green...

|

... watching the turgor pressure come up in newborn leaves...

|

... while a carpet of color slowly unfurled itself over the forest floor. Last month, the ground was a monochromatic mush of last season's leaves dissolving into earth. Where there had been only decay, life crept forth and clung tightly, refusing to yield, or even be ignored.

|

Beyond the woods, the land opened into farm country, a place desolate and dull in winter, now lush and thriving. We tramped through grass so new we could smell it growing, meandering through the fields to the fence at the far side to visit the cows newly sent to graze.

|

Our walks took us back to the forgotten gardens outside the castle walls, to the duck pond we found frozen the day it snowed. The rose vines we had discovered there, and which I feared dead, were swollen with new growth. When they bloomed, the arching canes would make a bower of blossoms over the abandoned duck house.

Back at Rheineck, specialists arrived and reclaimed bits of the formal garden. Daffodils appeared in the courtyard; the fountains were cleaned out and repaired. A pressurized hose blasted years of decayed leaves off the paths, and we learned the paving stones were more than brown but blue and green and red.

|

Spring is the time of year to pause and take a good look at your surroundings. Nature's resurrection, the triumph of Life over Death, Spring over Winter (certainly reason enough to come out of whatever cave you've spent the winter), tends to inspire housecleaning, or at the very least, a little personal introspection. Where am I? Is this where I want to be? Where am I going? How do I intend to get there? And when I do get there, what will I do?

Our walks were more than an exploration of our hillside and a desperation for some other color than brown. It was time to take stock. Of the eight of us who had arrived in Germany last October, only three were left. We were starting to get requests from those who had left for Christmas to please ship their belongings home to the States. Ian and I had plans to visit the States briefly in July; if we left Europe, would we be asked to delay our return to Germany? Who would be left to ship our things back to us?

It was not an easy decision to come to. Sometimes, even now, I wonder how we dared to walk away. We would be leaving Rhieneck only fractionally restored, leaving the Byteburg while it was still a caterpillar, still full of promise for great things as yet unrealized. But the timelines had stretched far beyond anyone's estimation and everything seemed snarled in German bureaucracy, something best left to those fluent in German to sort out. If all we could do was wait, it seemed more productive to wait elsewhere and more fair to wait off payroll.

|

The rest of April we spent packing, both for us and for those who had returned to the States before us. We pared our things down to what we could carry in four suitcases and two carry-ons and shipped everything else: a total of thirty boxes containing everyone's books and movies, music and clothes, souvenirs and little necessities, all indexed and catalogued for customs inspection and packed to survive a sea voyage. The project ate several rolls of packing tape and at least one Sharpie marker.

We left the boxes in the old downstairs kitchen with strict instructions and duplicate paperwork. We left the suitcases in our empty room. And, slinging backpacks over our shoulders, we made our way back to the Bahnhof. For there was no way we were going to leave Europe at the height of Spring without exploring first. Besides, I would be 25 tomorrow; we would celebrate my birthday in Italy.

|